Story of Balsamic Vinegar

A tradition of taste that lasts centuries

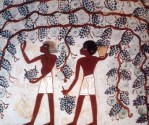

Evidence of the massive use of vinegars and grapes must as well as apple, date palm and fig musts have been traced and dated back to the third millennium B.C. in civilizations of the Near East like Mesopotamia, Egypt, Palestine and later also Greece and Rome.

Evidence of the massive use of vinegars and grapes must as well as apple, date palm and fig musts have been traced and dated back to the third millennium B.C. in civilizations of the Near East like Mesopotamia, Egypt, Palestine and later also Greece and Rome.

A huge quantity of vinegar was used for preservation of the food and as dressing for rich and poor people, as medicine and up to the Modern Age it is still being considered the most powerful acid in nature.

A huge quantity of vinegar was used for preservation of the food and as dressing for rich and poor people, as medicine and up to the Modern Age it is still being considered the most powerful acid in nature.

After the conquest of Magna Graecia by the Romans and the first trade negotiations, the wine and vinegar culture became popular in Rome, which could boast of its strong business and cultural development and favoured a great growth of the food and wine industry. Under the Roman rule of the Mediterranean, the acetabulum (the vinegar cruet) was found on any dining table and the production of “special” and “aromatic” vinegars became widespread.

The roots of Balsamic Vinegar were found in the cooked must and an Egyptian funerary painting demonstrates that the production of the first sweetener used in the Mediterranean area dates back to long time ago, at least to 1000 B.C. Even for the cooked must the Roman era was a great one and there was a specific verb referring to this action called defrutare.

The agronomist Lucius Columella, when describing the ideal farm in the first century AD, mentions a cella defrutaria (a cellar where wine is boiled). Virgil (70 B.C.-19 B.C.) in the first book of The Georgics where he describes a farm in his home town Mantua, which was part of the Emilia region in the Roman era, writes: “it is autumn… his wife solaces herself with singing over her endless labour, running the noisy shuttle through the warp, or boiling down the sweet juice of grape must, on the fire, while skimming the cauldron’s boiling liquid with a leaf”. Lucius Columella in his De Re Rustica writes: “this (the cooked must), once cooled, is poured into the barrels so that it can be used after one year”.

This evidence may prove the modern balsamic vinegar originates from the Roman era, but it is not possible to know the characteristics of these products, probably since there was a wide range of recipes with many local differences and in the Emilia region there was a popular and highly appreciated autonomous tradition. The love for strong and clear flavours, which were typical of the classical age and late Antiquity, may lead us to believe that these products, despite being the predecessors of the modern vinegar, had different characteristics.

This evidence may prove the modern balsamic vinegar originates from the Roman era, but it is not possible to know the characteristics of these products, probably since there was a wide range of recipes with many local differences and in the Emilia region there was a popular and highly appreciated autonomous tradition. The love for strong and clear flavours, which were typical of the classical age and late Antiquity, may lead us to believe that these products, despite being the predecessors of the modern vinegar, had different characteristics.

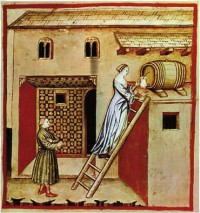

In the Middle Ages, especially in the south of the Alps, vinegars were still much used and more importantly wooden barrels started to become popular; they were Celtic containers, quite unknown in the Roman era. Due to sea trade, terracotta amphoras were the most used.

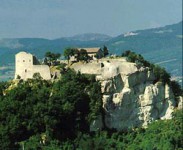

The vinegar produced in Canossa in the Middle Age certainly is the most famous in the antiquity. It was produced by Donizone, a Benedictin monk who lived btween the XI and XII century. This represents the first written testimony on balsamic vinegar.

The vinegar produced in Canossa in the Middle Age certainly is the most famous in the antiquity. It was produced by Donizone, a Benedictin monk who lived btween the XI and XII century. This represents the first written testimony on balsamic vinegar.

In his chronicle “Vita Mathildis” he tells that during a stop in Piacenza in 1046, the king and future emperor Henry II of Germany sent one of his messengers to the marquis Bonifacio of Canossa, Matilde’s father, “since he wanted some of that vinegar that was praised to him and that was produced in the Canossa court”. In this story there is no mention to the word “balsamic” but there is indeed the evidence of the fact that even in those times that vinegar was considered so important to be given as a present to an emperor who knew about its existence. Nevertheless we still have to wonder if it is correct to say that it really was our traditional balsamic vinegar considering the times and the place where this recollection is set. Is it really possible that such a refine product was born in a medieval manor-house by means of rough inhabitants of a castle, always ready to get to war? Balsamic vinegar is in fact a product of a totally different culture, matured in a refined environment.

At the beginning of the 14th century during the renaissance era, food preferences changed radically and new trends developed in Italy and all through the European noble courts. Lords’ meals became a time to expose their wealth and these sittings became more and more luxurious. On the table you could find lavish cutlery, pieces of silverware and even dishes were served with some “special effects”: flying doves, games of light with fireworks and so on. Serving dishes then, started to follow a fixed hierarchical scheme. Also condiments underwent a remarkable change due to the availability of eastern spices and new tests.

The sweet and sour revolution of the aristocratic food industry in the Renaissance led balsamic vinegars, since there were many recipes, to success. They were expensive and refined condiments able to sweeten new dishes without being too acid. Modena and Reggio Emilia soon became famous production areas and step by step balsamic vinegar turned into the highest quality product of the Estensi Court (the dukes of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia), well-known all over Europe. This condiment was believed to act as a medicine as well; legend has it that in 1500 the duchess of Ferrara, Lucrezia Borgia, asked for it to soothe her labour pains.

The sweet and sour revolution of the aristocratic food industry in the Renaissance led balsamic vinegars, since there were many recipes, to success. They were expensive and refined condiments able to sweeten new dishes without being too acid. Modena and Reggio Emilia soon became famous production areas and step by step balsamic vinegar turned into the highest quality product of the Estensi Court (the dukes of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia), well-known all over Europe. This condiment was believed to act as a medicine as well; legend has it that in 1500 the duchess of Ferrara, Lucrezia Borgia, asked for it to soothe her labour pains.

In 1598, when Modena became the capital of the Estensi dukedom, the dukes brought their vinegars from Ferrara and their integration with the typical recipes of the local noble families was so successful that the dukes took possession of the condiment. Probably the merging of these traditions gave birth to a balsamic vinegar whose characteristics and production methods were very similar to the present ones. It is no coincidence that from that moment on, historical information has been more detailed.

In 1598, when Modena became the capital of the Estensi dukedom, the dukes brought their vinegars from Ferrara and their integration with the typical recipes of the local noble families was so successful that the dukes took possession of the condiment. Probably the merging of these traditions gave birth to a balsamic vinegar whose characteristics and production methods were very similar to the present ones. It is no coincidence that from that moment on, historical information has been more detailed.

In 1597 the court procurator Giovanni Francesco Vezzali wrote a letter to the court farmer Ercole Estense Mosti to purchase Trebbiano for the acetaie (the place where barrels are kept and vinegar ages). One year later the ducal governor Giovanni Battista Contugo, in his letter to the ducal Chamber, wrote he had found the right grapes for the acetaie. The fact the duke was interested in the balsamic vinegar means that he could taste ripe vinegar, so probably vinegar barrels had been there for long time. Based on written documents, the term balsamico (balsamic) was first mentioned in a register of the ducal cellar in 1747; according to the document, the vinegar had to be moved from a secret cellar to the Camera del Prato (meadow room), an historical place for the balsamic located in the western tower of the ducal palace.

In 1764 the Great Chancellor of Muscovy, sent by the zarina Catherine the Great on a diplomatic mission to the European capitals, arrived in Modena and asked to send some bottles of balsamic vinegar to Moscow. In 1792 at the coronation of the Archduke Francis II of Austria, the Duke Ercole III of Este sent him a small bottle of his aged vinegar as a gift.

In 1803, under the French rule, the batches of the ducal vinegar were sold at an auction, but they were bought by the local aristocrats to enrich their acetaie and by doing so they preserved this heritage. Thanks to the dukes, the acetaia was partially reestablished but in 1862, with the coercion to the Kingdom of Italy, king Vittorio Emanuele contributed to ruin the ducal acetaie, because he sent the best barrels to Moncalieri where they were damaged by the mould caused by the bad climate. That was the first time that barrels of vinegar were the “war booty” of a winning King.

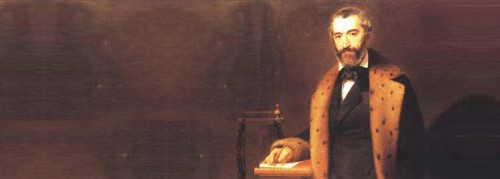

This “theft” increased the value of balsamic vinegar; in order to save the barrels stolen by the king, the enologist of Casale Monferrato asked the passionate and expert producer Francesco Aggazzotti (1811-1890) how to deal with the batches of vinegar. The answer, given in a famous letter, is the first and extensively written description of the production cycle and it was used as a reference for the product specification of the Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena (Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena).

This “theft” increased the value of balsamic vinegar; in order to save the barrels stolen by the king, the enologist of Casale Monferrato asked the passionate and expert producer Francesco Aggazzotti (1811-1890) how to deal with the batches of vinegar. The answer, given in a famous letter, is the first and extensively written description of the production cycle and it was used as a reference for the product specification of the Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena (Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena).

From that moment on, the tradition of balsamic vinegar was carried forward by the local noble land owners, who had always had their own acetaie, even if they were not as popular as the ducal ones. This tradition was accompanied by the farmers’, who could not afford to produce such a refined condiment but continued to develop what was known as the recipe of medieval balsamic condiments and what is known today as the Aceto Balsamico di Modena I.G.P.

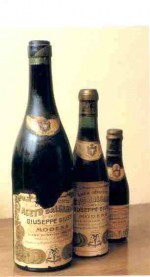

Up to the 1850s balsamic vinegar was a local speciality and was unknown abroad, except for some connoiseurs; after the unification of Italy, the growth of the national trade and the increasing presence of Italian products in Europe favoured a commercial production. In 1861 the vinegar of the Giusti family was shown at the Florence Exposition. In 1885 and 1891 balsamic vinegar was awarded with many prizes in Vienna and after the expositions in Genoa and Brussels the Emilia products, especially balsamic vinegar, were internationally famous.

Up to the 1850s balsamic vinegar was a local speciality and was unknown abroad, except for some connoiseurs; after the unification of Italy, the growth of the national trade and the increasing presence of Italian products in Europe favoured a commercial production. In 1861 the vinegar of the Giusti family was shown at the Florence Exposition. In 1885 and 1891 balsamic vinegar was awarded with many prizes in Vienna and after the expositions in Genoa and Brussels the Emilia products, especially balsamic vinegar, were internationally famous.

In this period the first producers followed the tradition but had their own recipe; for this reason there were many types of balsamic vinegar of Modena. Only in 1967 when the Consorteria dell’Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena (the association of the Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena) was set up, a common production method was established basing on the letter written by Mr. Aggazzotti. Besides this, some quality criteria that need to be respected were identified, even if producers are free to give some variances to their product. In the globalization era, the ancient history of balsamic vinegar prevented the product from being “depersonalised”, this means that nowadays you can find as many balsamic vinegars as their producers and each bottle is unique.

To anyone interested in deepen centenairan history of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modenq should read the essay "Le Terre del Balsamico" written by medievalist Renata Salvarani. It is available online in various websites and accessible in the Library A. Delfini in Modena.

To anyone interested in deepen centenairan history of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modenq should read the essay "Le Terre del Balsamico" written by medievalist Renata Salvarani. It is available online in various websites and accessible in the Library A. Delfini in Modena.

We can also arrange guided tours of our Acetaia reporting topics of your interest about Traditional Balsamic Vinegar. All interest could contact us directly from this web-form.